We all know a “great” movie when we see one: the films that are perpetually in the American Movie Classics canon; the films that were preserved (or nearly destroyed) by the contentious Ted Turner; the films whose unquestioned greatness is constantly championed by the American Film Institute and Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, who refuse to let us forget that The Godfather is indeed a damn fine movie; the films, and scenes, that have seen countless parodies, spoofs, satires, and homages throughout the years. The films that esteemed critics, scholars, filmmakers, and movie buffs all agree are great. Welles, Spielberg, Scorsese, Hitchcock, Kubrick, Fellini, Bunuel, Bergman.

Frankly, it gets tiresome.

The “great” movies, as we call them, are great for one of two reasons: because they are truly innovative or spectacularly well-made – a true work of art, one might say — or because the film has been acknowledged as great for so long people stop questioning it.

But the one quality that can lead to a film being deemed “great” is its ability to influence; great films take influence from other films, and one may assume that the film influencing the great film must have some great qualities itself, right?

A scene from a film that being easily recognisable or frequently referenced suggests that the scene has some great merit to it (in the case of Plan 9 From Outer Space, that greatness is of the camp variety), thus its acceptance and acknowledgement by so many people. Right?

Could Ridley Scott have made Alien without camp-classic Planet of the Vampires coming before it?

Alien (Scott, 1979)

What about the films that inspired the great films? Those quiet, often esoteric films whose reputations may not be as glamorous as, say, It’s a Wonderful Life but whose aspirations are tenacious nonetheless; whose camerawork isn’t as ostentatious as a David Fincher film and whose propensity for political and social commentary trumps that of its contemporaries (one may call these films “literary”).

Their importance on classic and current cinema is understated but substantial — who knows what Aronofsky’s acclaimed Black Swan would have been like without the atmospheric influence of Polanski’s densely foreboding Repulsion. And without the technological achievements implied in the camp-classic Planet of the Vampires, Ridley Scott may not have crafted the same iconic scenes in his slow-burning classic Alien.

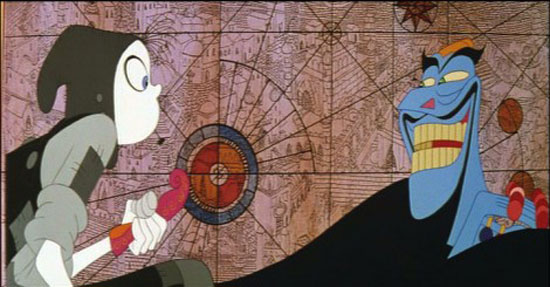

These quietly important pieces of work have left celluloid footprints for decades on filmmakers and films we all know, but the inaugural works from which those footprints emerged too-often go unnoticed. (Ever heard of The Thief and the Cobbler? No? But you’ve heard of Aladdin and Pixar?).

Films that represent significant influences on other great films and filmmakers

These are some of the best of these quietly important films. I’ve concentrated on the mid-fifties to one film from the early seventies simply because these are the ones that have received less recognition (a couple have received great admiration in recent years but remain unknown by the great majority of film-goers).

These films represent significant influences on other great films and filmmakers, whether it is in tone, atmosphere, story, or mise-en-scene. A work of art is often an amalgamation of great influences; these are those great influences…

Night Of The Hunter

Dir. Charles Laughton (1955)

Perhaps the most well-known film on this list, Night of the Hunter, the only film directed by Charles Laughton, effectively killed its director’s career. Motifs of German expressionism and surrealist imagery lend the film its ethereal aura which wavers between warm daydream and sordid nightmare; hyperbolic shadows jeté across forlorn landscapes, carefully adumbrating danger with a delicate precision that still retains an ambiguous quality — we never truly believe something dire will happen to our protagonists even when logic and practicality suggest otherwise.

Even after the film’s shocking first murder we as viewers don’t quite believe what’s transpired before our eyes. The characters in Laughton’s film, a widowed mother (Shelley Winters) and two young but resourceful children (Billy Chapin and Sally Jane Bruce, both unforgettable in their heavy roles) are caught under the infectious spell of a travelling preacher, Reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum in his greatest and most subtly insidious performance).

We quickly figure out that The Reverend is a killer who is after a great sum of money secretly left to the widow, but he seems to lack some of the more obvious tendencies and qualities that most cinematic villains have; he’s quiet, self-assured yet contemplated, at once calculating and then affable.

The words “love” and “hate” are infamously scrawled across his knuckles. Mitchum’s dialogue is clever and fitting, but it’s his acute annunciation of particular words (“Hellooooo, chil-dren”) hidden within his southern drawl that makes the Reverend Powell such a nightmarish character.

Of course he isn’t a realistic character in the literal sense, but within the context of Laughton’s picturesque dream world Mitchum’s portrayal of The Reverend is flawless. The inconsistencies within his demeanour are perfectly consistent with his constant shifting of faces. (Kim Novak used similar tendencies in her portrayal of the inured Judy/Madeline and she was initially criticised for being “wooden,” but how else is someone who is living behind a façade supposed to behave?)

There are a handful of starkly beautiful shots from Night of the Hunter, fiendishly unrelenting in their depiction of soiled innocence, that belong in the MoMA. The contrast in Stanley Cortez’s photography implies an inevitable corruption but leaves slivers of hope.

Look at the scene of the body in the lake: hair flowing in the current like tendrils, seaweed clinging to the corpse. It’s a terribly morbid shot and Laughton’s camera lingers, yet it’s never a gruesome or disgusting scene. The body almost looks peaceful sitting in the water, as if waiting for something or someone. Rarely has death looked so beautiful.

Perhaps the shot that best transcribes as a still shot is the one in which The Reverend chases the children up a staircase in an austere basement. It’s filmed from a profile (side view) so we see his outstretched hands come within inches of the children’s napes. It’s a sudden explosion of suspense in a film that’s very deliberately paced up until that point. The second half of the film begins here as the children take off down the river with Powell in pursuit. The rest of the film wrecks your nerves.

Laughton’s masterpiece Night of the Hunter shows Hitchcockian sensibility in its use of suspense and glimmers of German expressionism but the final product, a conflation of input from some of the best artists in the film industry, is a wholly unique experience.

Laughton’s eerie meditation on innocence and evil stands beside Citizen Kane as the benchmark for criminally overlooked movies at the time of their release.

David Lynch has credited Night of the Hunter as a stylistic influence on his neo-noir masterpiece Blue Velvet as well as his Cult TV show, Twin Peaks, a show many (myself included) consider to be one of the best, if not the best, written show of the last quarter century.

A Face In The Crowd

Dir. Elia Kazan (1957)

Elia Kazan had one of the most sterling careers of any Hollywood filmmaker, a mostly immaculate string of critical and commercial hits that often went starkly against the grain of contemporary Hollywood politics.

Perhaps best known for his non-realistic On the Waterfront, a film whose achievements are impossible to overstate: the method acting forever altered the impact of performers (Marlon Brando earned the Oscar for Best Actor and the unparalleled Karl Malden was nominated—and should have won—for Supporting Actor while the always compelling Lee J. Cobb was also nominated for Supporting Actor ); the set pieces are grungy and dank, not shimmering and romanticised, and, along with the mimetic sound design, envelopes the audience in a feeling of inclusiveness; the story, an allegorical defence of Kazan’s cooperation with the House Committee on Un-American Activities and McCarthism, shows how one can retain his pride and honour even when “ratting out” your friends.

On the Waterfront will probably stand as Kazan’s greatest and most influential contribution to American cinema, although one could possibly make a claim that East of Eden or A Streetcar Named Desire has also had a lasting impact.

One of Kazan’s lesser-known works, the socially-minded A Face in the Crowd, received mixed reactions when first released (as is the case with most great films) but launched the career of its star, Andy Griffith.

Griffith, whose “Andy Griffith Show” set the standard for situational comedies and blue collar television programmes and whose Matlock preceded the legal drama explosion of the 1990s, never had a role as lush as Lonesome Larry Rhodes, a hard-drinking folk singer and amateur comedian who is thrust into the spotlight after one of his jailhouse performances is clandestinely recorded by a radio programme called A Face in the Crowd. Lonesome soon develops a huge following, particularly with housewives and other inured townsfolk who can relate to the radio persona’s parables and rebellious songs.

But life in the limelight isn’t all one may hope for and Larry, known by everyone else as Lonesome, seeks serenity at the bottom of his liquor bottle, desperately drowning in his disconnection.

Kazan warns against a reliance on media and television personas and his message has never ceased to be relevant. The Village Voice’s J. Hobberman says, “A Face in the Crowd is essentially a political horror film. It’s not funny enough to work as satire, a bit doggedly literal for allegory, yet too hyperbolic to convince as drama. Nor was it a hit.”

Today’s scholars may try to insert a Regan-type character in the role of Rhodes, whose political rise initially stems from his small but dedicated following eat up everything he says, even as his ideals change considerably, but the honest truth is any political leader could fit into the Lonesome Rhodes mould, an idealistic dreamer uncompromising in his thoughts and actions who succumbs to the temptations of fame and glory and subsequently loses himself.

In typical Kazan fashion, the allegorical elements are ambiguous enough to always be relevant and aren’t fastened to one particular time and place. Similar to On the Waterfront, the themes are universal and the players do a fantastic job of creating empathy. Few Western directors could tell a compelling and relevant story like Kazan could, and A Face in the Crowd is as timeless as any of his films.

Peeping Tom

Dir. Michael Powell (1960)

Released the same year as Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, Peeping Tom tries to humanise a sociopath and, while not making him truly likeable, at least attempts—and mostly succeeds—at delving into the mind and soul of a man deranged and lonely, whose mental degradation cannot be simply explained by “daddy issues” or “peer pressure.”

Enjoying only a sliver of Psycho’s success and very little of its critical appreciation, Powell’s last great film was declared dangerous by prudish critics and cast aside, back in the dark where film viewers are more comfortable. Powell put us behind the camera, in a way, and allowed the viewer to stand in the light bedside the killer. Showing us the deaths from a first-person perspective gave us a glimpse of what it’s like to steal a human life.

Mark Lewis (Karl Boehm), a skilled cameraman and cinematographer who works for television and film and takes pictures of models in his spare time, kills women while recording them on his camera for a documentary he is making, the main focus of which is the human fear response.

We know he must be good at his work as we can see the technical superiority of the footage he is watching, however vile it may be. Whereas Anthony Perkins’ Norman Bates possessed a likeable if shy demeanour only to reveal his sinister secret during the film’s gut-wrenching climax, Mark seems odd from the get-go, talking in circles in his hard-to-place accent, nervously ticking, creepily ogling other characters like a misguided flâneur.

While the ending to Hitchcock’s paramount horror film has become commonplace in the world of movie knowledge, it still remains compulsively watchable and somehow suspenseful, all of the master’s techniques and furnishings holding up well after five decades.

Powell’s film, on the other hand, has dated on a technical level but remains fresh as a dissection of incomprehensible loneliness; it’s a visual film and the camerawork and imagery effectively convey a certain obsession.

The scene is shot on Rathbone Street in Fitzrovia, and the pub seen in the shot, The Newman Arms, is still there.

Powell and cinematographer Otto Heller fill the screen with stunning imagery and lush colours. Powell’s direction is nearly flawless. In a scene towards the beginning of the film we see the camera slowly pull back as Mark watches his footage of a victim screaming for her life. Soon the head of the victim on the screen is the same size as his head in the foreground thanks to some lens manipulation and we see Mark once again confusing real life with what is on screen.

The film’s first-person scenes were an obvious influence on Bob Clark’s Black Christmas and John Carpenter’s Halloween. The idea of snuff films inspired Joel Schumacher’s 8MM and arguably the Hostel films, although the latter borrow none of the artistic integrity of Powell’s film. It was also a major inspiration to Martin Scorsese, who helped promote the film in the 1970s and earn it more appreciation.

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

Dir. Peter R. Hunt (1969)

The best non-Connery Bond film, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was the meanest and most emotionally fulfilling Bond outing until Daniel Craig earned his license to kill in 2006’s Casino Royale.

The first five Bond films – Dr. No, From Russia With Love, Goldfinger, Thunderball, and You Only Live Twice – all of which stared Sean Connery, developed a certain sense of light corny humour, which would evolve into a camp appeal in Connery’s final official Bond outing Diamonds are Forever and the subsequent Roger Moore films, that made the absurd amount of violent action and seduction seem comedic, not masochistic and misogynist.

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the only Bond outing to feature George Lazenby as 007, dismissed much of the silliness in favour of dark humour and gripping suspense. The film is deliberately paced and Lazenby portrays Bond as much more vulnerable than Connery did; many have reaffirmed that the film’s story and visuals are amongst the best in the entire Bond series but the film may have been better had Connery played Bond instead of Lazenby.

While Connery may be the first and most beloved Bond, he would not have been right for this Bond; 007 trades hits with various strongmen but a feeling of imminent danger lingers throughout most of the action sequences, as if Bond may actually lose the fight, or something legitimately bad may happen to him.

Connery’s Bond was nigh-invincible and always infallible, whereas Lazenby seems frightened in certain sequences. For instance, look at the mountainside escape: Bond is hasty, almost sloppy, and loses a ski during the pursuit but he’s able to get the upper hand on his pursuers using quick thinking and some improvisation. When Bond hides from the henchmen, the look on his face suggests that he believes he’s in danger, or incapable of escaping. We know that he’ll survive and go on to star in many more films but in the context of this film, without thinking of the subsequent Bond outings, Lazenby’s 007 is the most believable and the most tragic.

Bond is out to stop Blofeld (Telly Savalas) from destroying the world, in case you wanted to know. But the destruction of the world is never a seemingly real threat, obviously. The film’s main emotional pull is Bond’s vulnerability. He is a much more trusting person here, but his naivety soon turns to hatred.

The film is slow for the first hour or so, allowing Lazenby some room to flesh out the seductive side of Bond (he’s borderline sexually deviant during a long stretch of scenes with some distraught but loose ladies in Blofeld’s hideout). Posing as a Scottish genealogist, Bond infiltrates Blofeld’s faux-clinical research facility. The majority of the film takes place here, building up the characters and creating emotional resonance only to shatter us later, similar to the extended poker scenes in Casino Royale.

The violence isn’t as cartoonish as other Bond films saves for a few well-placed shots during the ski pursuit. One memorable shot of a would-be intruder strung up in his climbing gear only further displays Blofeld’s coldness, while another scene, in which Bond clings to a cable car, shows off Bond’s persistence.

Bond films don’t often receive criticism for their violence, since it’s usually shown in an aside manner without too much emphasis on gore, but the scene in which Bond rescues his wife-to-be from Blofeld’s lair with the assistance of her father shows the darker side of Bond as he mows down countless henchmen by way of gun, grenade, knife, fist, and nail, showing nothing could possibly be mistaken for mercy. He’s no longer an agent of MI6 out to promote justice but rather a vengeful assassin; Craig’s Bond probably took copious notes.

Of course the most controversial aspect to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is the wedding of Bond to Tracy di Vicenzo (Diana Rigg), daughter of crime syndicate leader Marc-Ange Draco. It’s an ill-fated marriage and we know it but the abrupt heart-breaking ending, with Bond clutching his wife whispering, “We have all the time in the world,” is the most emotionally draining and hardest earned moment in the entire franchise until Daniel Craig clenched his ill-fated lover in Casino Royale.

The film treats this as Bond’s first encounter with his sometimes arch-nemesis Blofeld, the brilliant misanthrope leader of SPECTRE, ignoring Donald Pleasance’s portrayal from You Only Live Twice. Played here by Savalas, Blofeld is more sinister, colder and more manipulative, and chooses to strike at Bond’s heart when his plans for world domination are foiled.

As you may have guessed, the film initially received mixed reviews but has become a fan favourite. Many fans and critics make the argument that the film may in fact be the best and deepest Bond film; it’s an interesting argument but not really an important one as the film isn’t better than From Russia With Love or Goldfinger, just a different one.

It’s a completely different monster than Connery’s seven official Bond films, which reviled in Bond’s invulnerability and creative dispatch of iconic villains, and it’s certainly more mature than Roger Moore’s camp outings (Remember the one where he’s in space? Or the guy with the metallic jaws? Or the metallic arm? Or when Bond runs across a river on top of crocodiles’ heads?).

It’s tough to say if On Her Majesty’s Secret Service paved the way for Martin Campbell’s Casino Royale since the films are almost forty years difference in age, but there are unquestionably numerous elements that Campbell borrowed to give his Bond film a serious, gritty tone. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service enters into emotional territory no other James Bond film previously dared to flirt with.

Easy Rider

Dir. Dennis Hopper (1969)

Dennis Hopper, perhaps best remembered for his daring performance as the rapist-addict-sociopath Frank Booth in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, initially cut his teeth as an independent film director. His most influential film, the buddy-road picture Easy Rider, set the stage for independent and count-culture films for ten years after its premiere.

Directed by and starring Hopper, a then-experimental drug user, Easy Rider told a simple tale of friends nicknamed Captain American and Billy who are searching for spiritual clarity and the meaning of freedom but instead find tragedy. Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper play the friends, a pair of bikers who traverse America and have a tough time making friends. Along the way, they meet an alcoholic lawyer (a young Jack Nicholson) who joins them only to receive a fatal machete blow to the neck.

The duo’s journey is unsuccessful as they’re greeted by a refusal for acceptance everywhere they go. At one point in the film the perpetually stoned pair asks what happened to America; in their own eyes they’re the only ones actually enjoying freedom and living life and everyone showers them with hostility, shunning the bikers’ lifestyle.

Their journey is the journey we all travel – that of life and death. There are themes in Easy Rider that are universal and resonate with all viewers: acceptance, individuality, doing what you believe in and fighting adversity of all kinds, finding clarity and finally finding yourself.

The film’s technical aspects aren’t amazing and the writing and acting can be splotchy at times (with the exception of Nicholson, fantastic as always) but the heart and soul of the film more than make up for the aesthetic flaws. The lighting, all of which is completely natural (Hopper claimed “God is a great gaffer”), helps foster an organic atmosphere.

But the two aspects to Easy Rider that certify its importance are the editing and the financing. Hopper was notoriously difficult to work with, partly due to his constant experimentation with drugs (he advised Lynch on Frank Booth’s use of drugs to lend an air of realism to the pseudo-surrealist Blue Velvet) as well as his flashes of perfectionism and refusal to corporate with editors. Hopper, who ran into continuous problems during production of both the technical and creative variety, apparently imagined Easy Rider as a vastly different film than what the finished product looked like.

The film had a long hard road between the wrap-up of filming and the final release because Hopper was inspired by Kubrick’s monumental 2001: A Space Odyssey (what filmmaker wasn’t? Really?) and envisioned Easy Rider as a three-hour epic using flash-forward devices. Although one use of a flash-forward does appear in the film in the form of a foreshadowing of the film’s tragic ending, the editing was done in secret by Henry Jaglom away from Hopper. The finished product, therefore, is actually largely the result of Jaglom’s editing.

Independent filmmakers such as John Cassevetes, Joel Schlesinger, Francis Ford Coppola (pre-Godfather), George Lucas (pre-Star Wars), and Sidney Lumet, among others, were able to get their independent projects green-lit thanks in part to Hopper’s film. Hopper helped rejuvenate an interest in American neo-realism, a genre that has always been associated with French and Italian cinema.

In his essay on Easy Rider as a great movie, Roger Ebert comments on one of the film’s most important scenes: “Many deep thoughts were written in 1969 about Fonda’s dialogue in a scene the night before his death. Hopper is ecstatic because they’ve made it to their destination with their drug money intact. “We blew it,” Fonda tells him. “We blew it, man.” Heavy. But doesn’t the movie play differently today from the way its makers intended? Cocaine in 1969 carried different connotations from those of today, and it is possible to see that Captain America and Billy died not only for our sins, but also for their own.”

Indeed. The pair finally find freedom at the end.

Charade

Dir. Stanley Donen (1963)

The once-ageless Cary Grant never had a role as comically rich as he had in Charade, an enigma of a film that has all the suspense and whodunit paranoia of a Hitchcock film but with a sharp sense of wit that the British filmmaker never quite mastered.

Grant plays an older gentleman who goes by many names, among them Brian, Peter, Alexander, and Adam, who woos the luscious Reggie Lambert (Audrey Hepburn). Reggie’s husband has been murder (thrown from a train) and now some bad men are after Reggie in hopes that she has a fortune left to her by her late husband. The espionage aspects feel like a Connery-era Bond film but the questions and coincidences are much less predictable and the solutions are much more satisfying; that’s not a knock against 007, simply a validation of Charade’s virtuosity.

The bad men (James Coburn, George Kennedy, Ned Glass, all well-cast) are truly villainous, not campy and certainly not cliché; one of them has a mechanical arm, and this was filmed a decade and change before Live and Let Die. But the real draw to the film is its sizzling dialogue and the not-quite lustful chemistry between the two leads.

The age between Grant and Hepburn is made into a joke within the film and Reggie is actually portrayed as the pursuer, quite an antipode to the seductive masculinity (or misogyny) of the early Bond films. Grant was always smooth, even as the wrinkles became more pronounced, but Hepburn doesn’t play sidekick by any means. She trades sharp one-liners with Grant throughout the film, refusing to be handled.

While Charade didn’t directly influence the Bond films or any of the other espionage films that came in surplus following Dr. No, it did foreshadow the coming action-comedy genre explosion of the 1960s into the 1970s.

One of the final films of Grant’s career, it’s a difficult film to place on a timeline of cinema; part Hitchcockian thriller, part spy flick, part Casablanca-esque romantic comedy, it sort of fell between the beginning of the end of Hitchcock’s prime years and the first Bond film.

The film saw rejuvenation in publicity as the Johnny Depp-Angelina Jolie 2010 flop The Tourist drew numerous comparison to the Grant-Hepburn film. But the lack of chemistry between Depp and Jolie proved that a great on-screen relationship isn’t easy to create.

(Charade was remade as The Truth About Charlie but Peter Stone, the writer of Charade, hated the film so much he refused credit and instead billed under one of Grant’s aliases.)

Planet Of The Vampires

Dir. Mario Bava (1965)

By most filmgoers’ standards, Mario Bava’s camp-classic Planet of the Vampires is not a good film. The acting is wooden, the special effects hit or miss, and the plot is pulled straight from an Ed Wood knockoff: a crew of space explorers receive an SOS call from a near-by planet find themselves trapped on a planet inhabited by zombies. Yet the film is irresistibly fun, ala Plan 9 from Outer Space, and its impact on science fiction is quietly substantial.

Many have argued that Ridley Scott’s big-budgeted B-picture-turned-masterpiece Alien took direct influence from Planet of the Vampires’ narrative and visual design; in Scott’s film, the crew of a space cargo ship receives a distress call from a nearby uninhabited planet and investigate. They take on an alien life form and, as you probably know, fall victim one-by-one to one of the most iconic and scariest villains in the history of cinema.

But whereas Scott’s film, which placed a heroine at the core of what seemed like a masculine story, shook off its B-movie beginnings and took a more artistic aesthetic, Bava’s film revels in its campy appeal. Scott’s film uses symmetry, similar to Kubrick’s camerawork in 2001, and deliberate pacing before unleashing its gruesome shocks. Bava’s film just sort of bounces around, having fun, not taking itself too seriously.

Produced on a shoestring budget, Planet of the Vampires doesn’t look as bad as one may think, but one may be tempted to compare the film’s dated look to the ageless appeal of 2001, Star Wars, A Clockwork Orange, or the silent-classic Metropolis. By such comparisons, Bava’s film doesn’t stand up. But maybe it doesn’t have to compete with such lauded films; honing the atmosphere of a pulp magazine cover brought to life, Planet of the Vampires is like a kaleidoscope of bold colours and outlandish set pieces, electronic beeps and screeching horror-film string scores.

Although dramatically lacking, Planet of the Vampires is fun way to kill an hour and a half and its appeal to filmmakers, such as Brian De Palma and David Twohy, cements its status as a quietly important film.

Repulsion

Dir. Roman Polanski (1965)

Darren Aronofsky’s erotic psychological thriller Black Swan, for example, channels Roman Polanksi’s classic gothic-horror masterpiece Repulsion in its depiction of a young girl battling Freudian demons.

Her inability to deal with the tremendous pressure and mental strain that her new found success warps her perception of reality and begins to tear apart her life.

As in Polanksi’s 1965 chiller, which has only grown in reputation and stature in the years since its release, the horrors that plague our young protagonist stem from sexual inexperience – a lingering childhood innocence she has yet to shed – and the unwanted advances of promiscuous men that manifest themselves as violent acts of lust. It is a disturbing film as well as a beautiful one that meditates on perfectionism as well as human sexuality.

Nina, a driven young ballerina who has recently earned top billing in her company’s production of Swan Lake, finds her strive for technical perfection hampered only by her inability to “lose herself” in her dancing – a repression of maturity that does not allow Nina to find the lust in her dancing that will allow her to become a truly great dancer and inhabit her characters.

Nina must not only play the pristine White Swan but also the wicked Black Swan that steals the White Swan’s true love and drives her to suicide. The goodness with which Nina leads her life – a life that is dictated by her overprotective mother (Barbara Hershey) – prevents her from fully embodying the wicked Black Swan.

Nina’s mother, at once caring and then cruelly overbearing, warns Nina not to push herself too hard for the role, to which Nina reminds her mother that she never even had a decent career of her own.

Hershey is equally heartbreaking and cringe-inducing as the has-been mom and the mother-daughter relationship provides a real human element to the story that serves as the emotional buttress that allows Aronofsky to take his film in surreal and horrific directions. Without this sense of reality to keep coming back to, a type of realistic root note which the film pivots around, the more fantastical elements of the film would not be nearly as terrifying or emotional resonant.

As is the case in Repulsion, Nina’s horrors personify themselves as sexual fantasies and grotesque mutilations, the latter of which was unfortunately shown far too extensively in the film trailers, ruining some of the more shocking moments of the film.

Nevertheless, there are more truly scary moments in this film than in the entirety of the Friday the 13th film series but it never relies on gore or makes your stomach churn.

It is more Alien than Saw, starting slowly and building suspense before it tears the rug out from under you and erupts in a cataclysmic mental breakdown.

Unlike Polanksi’s film, which is a sombre exercise in art-house horror that never really gives us a chance to get to know the mentally warped female character and therefore cannot expect us to sympathise with her, Black Swan gives us an empathetic character we can relate to, whose desires and fears reflect those that every artist faces.

The Thief And The Cobbler

Dir. Richard Williams (1993/1995)

Over thirty years in the making, Richard Williams’ would-be opus, a fantastical peregrination, preludes Disney’s Aladdin in its depiction of a young Arabian thief following a prophecy and trying to save his city from sure destruction and blends whimsical sound design with intricately layered animation to create one of the most complex visual experiences every attempted by an animation studio.

The two titular characters, a kind-hearted cobbler named Tack and an ingenious but unlucky thief, both mute, fall into the middle of a dastardly scheme to send a war machine, led by a horde of one-eyed monsters, into the Golden City in which our duo resides. They set off Goldberg-esque chain reaction which eventually leads to their saving the city and becoming heroes.

The plot is as linear as any subsequent Disney film but the main draw here is the stunning animation – and I mean you will literally be stunned, as if struck by a sudden electronic current; it’s that good. Full of optical illusions, the visuals cannot really be described by words, which makes a writer’s job particularly difficult when discussing The Thief and the Cobbler, and while the terms “optical illusion,” “combustion,” “lucid,” “dream-like,” “passionate,” and “self-assured” don’t begin to do the film justice, they’ll have to do.

Nothing is concrete in the film as the Golden City follows logic wholly unique to its inhabitants: rooms collapse into themselves, writhe as if being rejuvenated, and resurrect as new structures; all characters seem to have been blessed with malleable spines as they jump and leap and twist like the cartoon characters they are, defying our notion of physics in ways most cartoons had abandoned in favour of attempted realism.

Williams’ film basks in its own animated glory. It knows it’s a cartoon and it takes every advantage of the possibilities exclusively enjoyed by animated motion pictures. Rarely have silent characters been able to emote so vividly as Tack does here. Our villain, ZigZag the Grand Vizier (voiced by Vincent Price, the only man capable of bringing a certain quirky dignity to such ghoulishly delicious lines as, “I conjure demons, and charm beasts! And birds of prey, too! Phido! But as you see, that’s not all I can do! Haha! Hee-hee! I have power over people, too, though they may appear complex. For me… they fall like playing cards… and I control the decks!”), plans to betray King Nod and Princess Yum-Yum and take over the city using his minion army.

It’s easy to see the influence these characters had on those in Aladdin but Disney’s film feels timid compared to this, as if it plays everything too safe and settles for good, whereas Richard Williams poured enough soul into his passion-project to knock the wind out of Aretha Franklin. Aladdin was considered innovative at the time of its release but its ambition pales in the shadow of The Thief and the Cobbler.

Williams’ nearly-lost film doesn’t pretend to be subtle in its aesthetics but beneath the psychedelic sheen of its loud visuals is a very simple story of honour. The 1993 majestic reissue, poorly re-titled The Princess and the Cobbler, tries to add in subplots about social class romance, capital punishment, and patriarchal frustration as well as four songs (the original has no songs) and essentially ruins the magic of Williams’ picture. Williams knew his film main focus was its aesthetic delivery. He didn’t pretend to inject secretive meaning buried within the simple narration. It’s a simple story; it doesn’t need to be complicated. It would get too messy had the plot been as tightly-wound as the visuals.

The film, whose production preceded that of Bakshi’s Heavy Traffic by several years, displayed the elegance and intricacy that animation was capable of. Bakshi’s film would similarly try to push the envelope of complex animation but got caught up in its own pretentiousness, spending too much time pondering its own importance and keeping its viewers distant. The Thief and the Cobbler, although spectacularly complex, is entirely inviting and easily accessible, another testament to its artistry.

Those who are interested in seeing the film as closely to its original intended version as possible should check out “The Thief and the Cobbler: The Recobbled Cut.” A passionately slaved-over fan restoration, “Recobbled” has received great enthusiasm from many of the animators involved with the original film, many of whom even contributed to the project. Anyone interested with a serious academic interest in film needs – yes, needs – to check it out. You can learn about film more by following the troubled production of Richard Williams’ would-be opus than most expensive fancy film schools can teach you.

Westworld

Dir. Michael Crichton (1973)

Anyone with an interest in science fiction is familiar with Michael Crichton, the creator of Jurassic Park, The Andromeda Strain, Congo, Sphere, State of Fear, the daringly anti-political correctness novel Disclosure (not science fiction but still fascinating), and the television series ER, among many others.

Crichton’s contributions to the science-fiction genre are impossible to overstate, and many people aren’t even aware of his first major motion picture, Westworld, a calamity of cowboys and hostile robots run amok.

In a technologically-advanced futuristic society scientists have created robotic organisms who look and act exactly like humans, albeit slavishly devoted and obedient humans. Richard Benjamin and James Brolin star as two middle-aged friends, Peter and John, who are visiting an amusement park called Delos (Peter for the first time), which is comprised of three “worlds” ala Disney World named WesternWorld, MedievalWorld, and RomanWorld.

Each world recreates a historical society using sophisticated androids designed with authenticity in mind. Our heroes choose to relive the old West at WesternWorld, where the women in the saloons are beautiful and know how to “service” customers and the men drink hard and are quick to throw-down with customers looking for a barroom brawl. Delos presents the opportunity to step back into time and rediscover yourself; it seems perfect.

In one of the many bars in WesternWorld, Peter has his whiskey knocked out of his hand by a stoic gunslinger with a stare that could bore holes in mountains (Academy Award winner Yul Brynner). Prodded by John to settle the matter, Peter confronts the gunslinger and abruptly finds himself drawing his pistol and planting several dead-ringers into the gunslinger’s chest. The body staggers backwards and falls, blood pouring out. John pats his buddy on the back and they laugh as bar patrons drag the body away.

When asked what would happen if one were to point a pistol (given to them by Delos) at a human and fire, John presses his friend to attempt to shoot him. The gun won’t fire, revealing a safety mechanism that only allows the gun to shoot non-living things. The androids are programmed to ensure a perfect vacation for the visitors: they always draw slower than the human counterparts, the girls never turn down the sexual advances of a patron, and humans can never be harmed by the robots. It should be easy to see the parallels between Issac Asimov’s works and Westworld, the former of which greatly influenced Crichton, whose film in turn influenced other science-fiction films as The Terminator and the adaptation of I, Robot.

One memorable scene shows how the Delos employees roll up in large vans and trucks to gather the corpses and damaged androids and return them to the lab where scientists repair what they can and scrap the rest. The androids are always being upgraded, always being improved upon to become smarter, faster, stronger, more advanced. The rapid progress of the artificial intelligence is adumbrating what would become Skynet in James Cameron’s Terminator series.

A computer virus seeps into the system, however, and the androids begin to malfunction; a snake bites John, a women turns down a guest, and the gunslinger, revived from his would-be fatal injuries, turns up in Peter and John’s room seeking revenge. Soon a guest is slain in MedievalWorld and the androids in WesternWorld open fire on guests. John is killed by the Gunslinger and the film’s half-hour climax begins as the Gunslinger chases Peter through WesternWorld and into the other parts of the park.

The film takes its time getting to the action but it’s worth it; in what could have been a thanksless role, Brynner makes the silent Gunslinger bleakly terrifying in the same vein of Arnold’s T-800 albeit with a ten-gallon hat instead of Ray Bans. The chase is well-paced and suspenseful. We’ve already seen one of our main characters die, why wouldn’t Crichton kill the remaining one as well? The Gunslinger proves tough to destroy, predictably. Like Michael Myers, the T-800, and Hal-9000 all rolled together, the android Gunslinger is intensely memorable due to his persistence despite his lack of visual pizzazz.

The incipient computer technology in Westworld feels at once dated and fresh, similarly to that in Alien. The film looks aged at times, as one may expect from a smaller budgeted film from the early 70s, but its terribly creepy foreshadowing of society’s dependence on technology, while not as philosophical or metaphysical as that in 2001 or Blade Runner, is still captivating. The Gunslinger hunting down his human folly plays like a direct ancestor of The Terminator and the early descriptions of a computer virus, referred to in the film as a “disease,” is further evidence of Crichton’s advanced understanding of technology.

If you enjoyed our look at these influential movies, you may also like:

18 Essential Horror Films From The 1960s & 1970s

At the age of 72, Ruth Gordon received the Best Supporting Actress Academy Award for Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby.

We celebrate a golden era for horror cinema in which we saw Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre emerge amongst many others.

10 Essential Giallo Films For The Beginner

A Beginner’s Guide to Giallo: author and genre expert Michael Mackenzie investigates the evolution of the Italian thriller with its distinct mixture of highly stylised violence, sex & horror.

Top 10 Films To Watch Before Going To Film School

The “reading list” for film students. Are you about to attend film school? Or are you thinking about a career in the movie-making business? The following ten films are essential viewing.

Top 10 Films Made Before 1930 You Have To See

They don’t make them like they used to. This top 10 discovers why that statement rings so true with a look at some classic films made before 1930 that demand attention.

10 Remarkably Quirky British Films You’ve Never Seen

Here we look at 10 remarkable British films, from war propaganda of the 1940s, sexual exploitation in the 1970s, and avant garde experimentation in the 1980s and 1990s that have fallen by the wayside. Forgotten films that represent the often unique talents of visionary British filmmakers that any fan of cinema should discover.

[…] on the excellent UK blog Top10Films. You can find my post, The Top Ten Quietly Influential Films, here. […]

Great post. Had never even heard of The Thief and the Cobbler, so I’ll have to check that out.

I’ve seen five of these choices (The Night of the Hunter, A Face in the Crowd, Peeping Tom, Easy Rider, Charade).

Unfortunately I’ve only seen a few of these, but now I have a list of films to watch. Thanks!

I have recently seen “Night of the Hunter” and loved it for its stunning black & white cinematography and its creepy use of lullabies/folk songs/hymns. And I just recently rewatched “Charade” also which I often watch as a entertaining thriller/comedy but never thought about its importance to the genre and/or cinema. Honestly I was surprised it got the Criterion treatment until I read the academic essay on it and now your post.

Any list with Westworld in is a winner for me!!

I must admit though that I have not seen most of these films. Which I believe is a shame

Great writeup and fascinating list, Gregory. I really should give ‘OHMSS’ a re-watch one of these days. I wasn’t sold on Lazenby as Bond but I’ve heard praises about the film itself (and reportedly it’s Nolan’s fave Bond flick).

I’ve noticed a great many typos in my post that I missed while editing. My computer crashed and I had to type into google docs, so many mistakes went unnoticed. I apologize for the unprofessional bits.

Also, anyone concerned with older films, feel free to shoot me a message at my site. When technology permits it, I love discussing film on the interwebz.

Also, De Palma DID NOT direct “8mm,” it was Joel Schumacher of “Batman’s Nipples” fame. I meant to correct that but did not. My mistake.

I have to admit to a slight gasp of surprise when I saw OHMSS on this list – an excellent list, by the way Greg. I remember watching OHMSS as a younger man and wasn’t all that impressed by it; even the fact that a fellow Australian was cast as Bond didn’t inspire me that much. It’s been a few years now, so perhaps a reassessment might now be in order.

For the scorekeepers, I’ve seen a grand total of three of these: Westworld, Charade (a must-see) and Easy Rider (my father in law is a former bikie, so it was almost a given that I’d see this at some point).

I have yet to see Night of the Hunter but certainly, it’s one of those movies that I really need to check out. Superb list and you obviously put a lot of time and effort into it.

Some wonderful films here. One that stands out for me is one I haven’t seen – The Thief and the Cobbler – very interesting story behind the making of that film which spans over three decades. I’m going to have to check out Richard Williams version.

Easy Rider ‘quietly important’? It’s spoken pretty loudly down the years IMHO. OHMSS has many good points, but influential – personally, I think that’s debatable. It’s also always irked me that it features THE most appalling dubbing, and a denouement in which master villain Blofeld turns up in an NHS neckbrace as if he’d wondered off the set of Carry on Spying. Still, full marks to Peter Hunt (and Louis Armstrong).

A very thoughtful list. Nice to see kazan’s pic on here. You just made me put a couple in my queue. Great job here..

With 36,000 votes on imdb, “Easy Rider” isn’t exactly a phenomenon. It’s quietly influential because it’s byzantine editing process brought more attention to how important a good editor is, as is evident by the vastly different versions of the film with and sans Hopper’s editing. Also, the use of natural lighting influenced Norman Mailer’s experimental films and most people think of it as a counter culture film-of-the-moment, but its troubled production–funding, marketing, etc.–is really the first example of an indie film.

“OHMSS” has some silly moments, as does every Bond film, but the ending is THE saddest ending pre-“Casino Royale.” Hunt does a good job of slowly building their relationship to something moderately believable, and she’s portrayed as tough throughout the film, which makes her sudden demise all the more potent. She tames Bond! If the neck brace is the low point of the film– and it is silly, although not as silly as the underwater car, running on alligators, dropping a wheelchair down a smoke stack, trying to blow someone up via room service, metallic teeth, Bambi and Thumper, anything in Die Another Day, or a base on the moon– than the film does a lot of things right. It showed glimpses of the darkness that would enter the series with Dalton, and Lazenby is by far the most human and flawed Bond. Perhaps that makes him a “bad Bond,” but it certainly makes him a compelling character nonetheless.

Yes, the dubbing sucks. Absolutely.

Easy Rider is a perfect fit with the title of this post. I wonder how different/better/worse the film would have been if Hopper had managed to retain more control over it. I definitely would have loved to seen his vision, the film through his eyes, as disturbing and blurry as that may have been!

A film which doesn’t quite meet up to this post but is definitely ignored more than it should be is “Waiting for Guffman” – Has that featured in any Top 10 Films posts? I also often go back to my Guy Maddin corner for these kinds of posts. I’d be interested to read a Top 10 Films review of The Saddest Music in the World 🙂

Lazenby, Connery and Craig are all my favorite Bonds because they seldom tread into that super-campy-Bond-is-a-cartoon-not-a-human territory.

A fantastic, fantastic piece. I love how you expound so much on each film and dig deep into what made them so important and ahead of their time. It’s a shame that these films get passed over for the more popular or contemporary versions because they’re often better than those that come after them.

What a coincidence, I’ve just reviewed Easy Rider this week! It really should be side by side with other classics on IMDB’s top 250…one of the best road movies I think, a period film, yet the unpredicability of who the guys meet on their journey is enjoyable.

Anyway, interesting list, good job highlighting some lesser known films.

from Chris

Thank you for adding Peeping TOm – one of the greatest horror movies and so advanced for its time!

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within.

I know some people hate mo-cap (but somehow seem to adore Tin Tin,) but this film was the first mainstream American CG film aimed at adult audiences, and the first to attempt photoreal human characters. It looks wonderful by 2001 standards, and many shots are far superior to the aforementioned Tin Tin.